Culinary medicine can improve nutrition knowledge in medical trainees

In a “first-ever” randomized controlled trial of a culinary medicine curriculum for US medical trainees, researchers found that practicing hands-on cooking can effectively increase resident physicians’ nutrition knowledge. Moreover, the study authors note the approach may be better than traditional classes in improving participants’ confidence in providing dietary counseling.

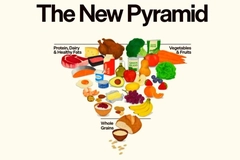

Culinary medicine combines medical education, nutrition science, and the culinary arts to promote wellness through meal preparation classes and hands-on cooking.

The research is timely — the Yale School of Medicine (YSM) team notes that only 26% of residency programs offer formal nutrition education.

Earlier this year, US Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said he wanted to make nutrition education compulsory in medical schools — or risk losing federal funding. Experts underscore the importance of embedding nutrition in public health policy and improving nutrition training for medical students, but urge that this should be grounded in science.

“We want trainees to learn about the benefits that certain foods have on cardiovascular disease, how to better manage patients’ health using nutrition, and to appreciate the importance and impact of dietitian referrals,” says first author Nate Wood, MD, assistant professor of general medicine and director of culinary medicine at YSM.

Disease-based program

The YSM study, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, compared the efficacy of hands-on culinary medicine with didactics-only nutrition training.

The researchers developed a longitudinal three-year curriculum on diet and disease for Yale Primary Care Residency Program residents. The curriculum focused on cardiovascular disease in year one, weight and obesity in year two, and diabetes in the final year.

“This three-year curriculum on diet and disease is important for our residents, especially in how it could translate to better care for our patients,” underscores study senior author Donna Windish, MD, and professor of general medicine.

“So many of our patients have at least one diet-related condition — type 2 diabetes, dementia, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart attack, stroke, obesity, kidney disease, fatty liver disease, etc.”

The study found that residents receiving hands-on training are more likely to discuss nutrition with their patients.All residents joined the curriculum, half watched video-based lectures (control group), and the intervention group participated in hands-on cooking classes. The participants completed surveys on attitudes, nutrition knowledge, confidence, and behavior before and after the sessions and again eight weeks after the class.

The study found that residents receiving hands-on training are more likely to discuss nutrition with their patients.All residents joined the curriculum, half watched video-based lectures (control group), and the intervention group participated in hands-on cooking classes. The participants completed surveys on attitudes, nutrition knowledge, confidence, and behavior before and after the sessions and again eight weeks after the class.

Expanding nutrition knowledge

Experts note that improved nutrition education is crucial for better healthcare, warning that training is inadequate. Although there is a growing awareness of medical nutrition in healthcare, Danone’s chief scientific and medical officer previously told Nutrition Insight that nutrition is not yet fully integrated into medical education.

Yale residents agree with these statements. In the study’s surveys, 83% of residents said they felt their training to date had not been sufficient to prepare them to provide dietary counseling to patients. Moreover, 94% said additional training would provide better clinical care for patients with diet-related diseases.

The YSM researchers reveal that both culinary medicine and didactics-only training can be “effective approaches to teaching nutrition” as nutrition knowledge expanded in both groups. For example, residents were more confident in educating patients on a heart-healthy diet or providing evidence-based information about heart disease.

The study highlights several differences between the intervention and control groups. Residents who participated in hands-on cooking classes reported feeling confident in all five domains of assessed dietary counseling, while the control group only noted an increased confidence in two domains.

Overall, Wood says that residents receiving hands-on training are more likely to discuss nutrition with their patients. The residents also said they were more confident in counseling patients on a plant-forward diet and reported providing nutrition resources to patients more frequently, eight weeks after the session.

“They are more likely to refer patients to dietitians, because they understand how important nutrition is, and they can help their patients find ways to eat affordable, accessible, healthy, delicious foods,” highlights Wood.

“Our findings show how hands-on classes aren’t just changing knowledge or attitudes,” he concludes. “They are changing behavior.”